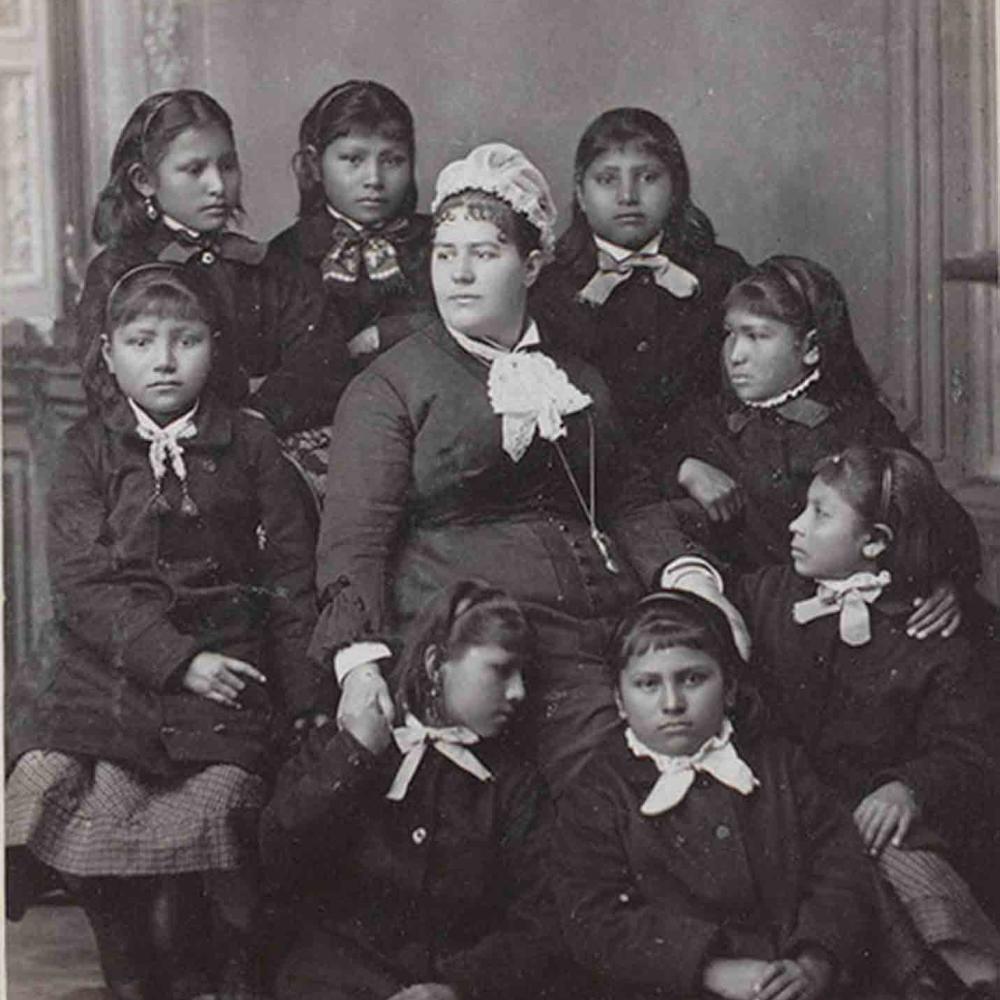

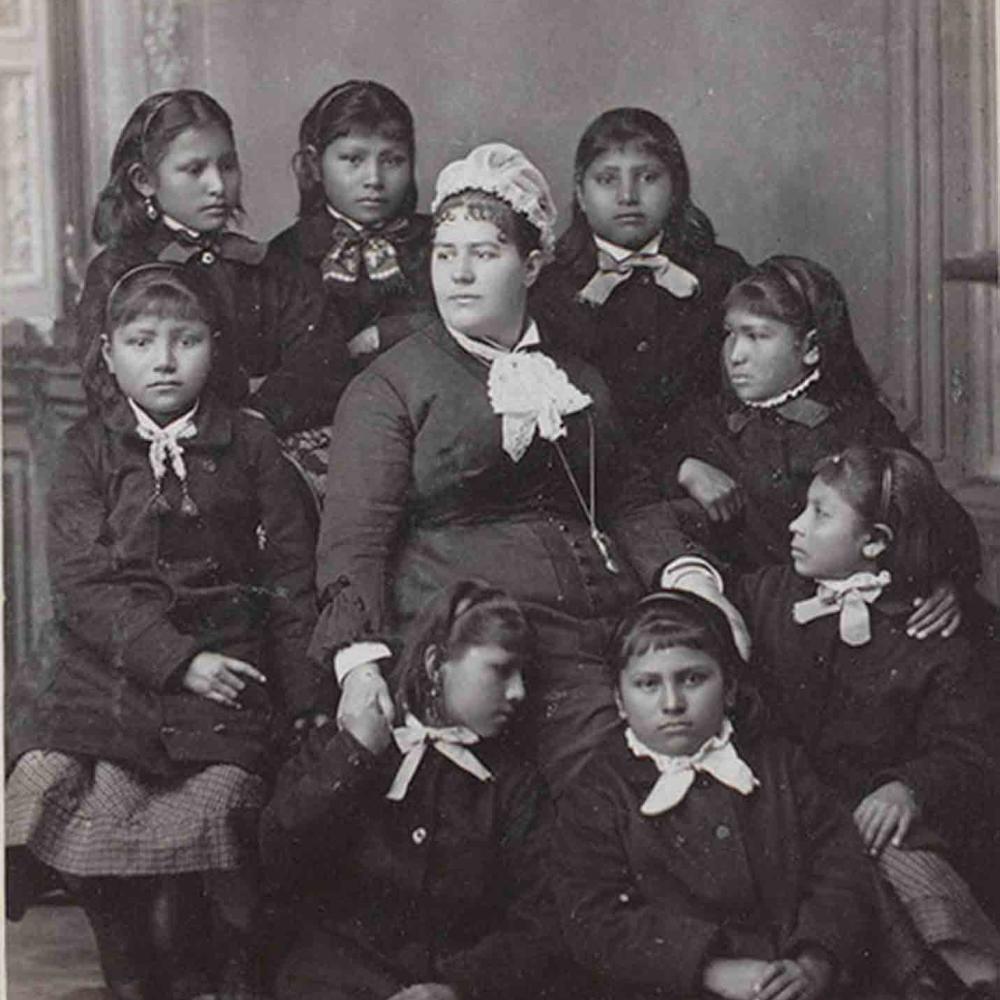

Teacher Mary Hyde with students of the Carlisle Indian boarding school circa 1880: Ann Laura (back left), Hattie Long Wolf (back middle), Rebecca Big Star (back right), Alice Wynn (middle row left), Grace Cook (middle row right), Mabel Doanmoe (bottom left), Stella Berht (bottom center), and Ruth (Looking Woman) (bottom right).

—Photo by John N. Choate, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Cumberland County Historical Society

Over the past 20 years, I have taught Native American history at community colleges, Christian schools, and large universities. I have encouraged my students to think critically, ask hard questions, and consult primary resources. “Don’t just read about what people said,” I tell them, “Do the hard work, go to the original source, and read them for yourself.”

In his edited collection of essays from the National Educational Association’s Department of Indian Education (1900–1904), Larry C. Skogen, a scholar long affiliated with Humanities North Dakota, has made that hard work a little easier. Skogen’s book, To Educate American Indians, includes speeches by white educators employed by the U.S. government’s Indian Service to teach Native American children. Some of the speeches resonated with me not only as a scholar but as a Hopi person, causing me to reflect on my family history and experiences as a teacher who has written extensively on the Indian boarding school experience.

When I lecture on Indian education, I often first introduce my students to the so-called Indian Problem, providing a lens for students to understand how non-Native people viewed Indians—not as an asset or benefit, but as a “problem” that needed to be addressed and eliminated. Not eliminated by slaughter or outright genocide (the U.S. government had failed in those attempts) but eliminated in the sense of eradicating culture and identity.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the U.S. government had stopped warring with Indian nations on the Great Plains and elsewhere, but the battle for the minds and affections of Indian youth continued at Indian schools. School officials, such as H. B. Frissell, principal at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural School in Virginia, believed schools played a major role in solving the Indian problem by making Indian youth discontent. “It is sometimes said of the schools off the reservation,” observed Frissell, “that when their students return they are not willing to live as their parents did. . . . A wholesome discontent is a most helpful sign.”

For the Hopi, the most widely known example of this comes from the life of Polingaysi Qoyawayma. Polingaysi spent four years, from 1906 to 1910, at Sherman Institute, an off-reservation Indian boarding school in Riverside, California. When she returned home, she judged her parents for living according to Hopi ways and customs (No Turning Back is her autobiography). Young people, especially teenagers, are already disposed to be critical of their parents. School officials such as Frissell used this to their advantage to turn Indian youth against their families.

Alienating Indian youth from their communities and cultures was accomplished by various means. At Indian schools, officials instructed students in math, science, history, and other disciplines. Teachers wanted their Indian pupils to see the supposed superiority of Western education while simultaneously becoming critical and doubtful of Indian teachings and worldviews. Male students learned trades and female students learned to be good housekeepers according to Western values. Some students also participated in sports and musical ensembles, while others used their skills in the English language to work in the print shop or as editors for the school newspaper.

In my office, a prized possession sits on a bookcase: a complete ten-volume set of The Red Man, the official student-written newspaper of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Hardbound and organized by year, the books recall happenings throughout the school year, motivational speeches, Native American stories, and alumni news.

“Every Indian school should have the newspaper,” William T. Harris, U.S. Commissioner of Education, remarked in his 1902 speech in Skogan’s collection. Telling his audience that Indian pupils should read “first that which interests him,” the commissioner further observed that the pupil will “go from that to the far-off events of the world, according as he grows in intellectual capacity.”

School officials did not encourage Indian youth to listen to their parents back home on Indian reservations. They did not encourage them to seek wisdom from their tribal elders or other knowledge-keepers about the world beyond their homelands. Instead, they wanted them to learn from newspapers and considered the printed word far superior to the oral tradition often spoken in one’s Native language.